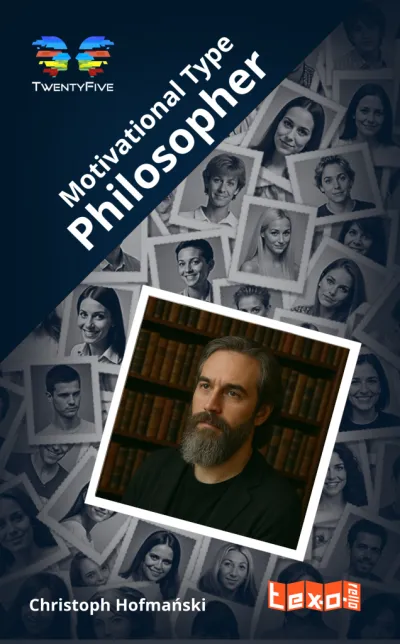

The Philosopher

Motivational Type

Christoph Hofmański

Before Christoph Hofmański (born 48) founded his consulting company under the name "Kommunikationsmanagement" in 1988, he worked as a marketing manager in an international IT company. During this time, the discussion about emotional intelligence began to become more audible. Guided by the question "What is a certain behavior good for?", Hofmański interpreted the bi-polar dimensions of personality psychology as existential, conflicting basic needs. This gave rise to the construct of "deep motivation" in the mid-1990s. In the work of the last 25 years, there has been a growing realization that we can better understand people if we bring the construct of basic needs into a multi-layered model that captures the "flow of energy" from drivers to situational behavior. Practical use in many coaching sessions motivated Christoph Hofmański to develop TwentyFive.

Persönlichkeitstypen

100

9783912062014

12.10.2025

English

1

The Philosopher

Philosophers are curious. They want to understand why or for what purpose something happens and how things are connected. Unanswered questions move them to perceive interesting objects from different sides and to change perspectives. It is important to them to act meaningfully. This book describes their particular strengths and competencies. It shows what is important to be satisfied with oneself and one’s life.

Leseprobe

When we use imaging techniques to observe what happens in the brain, we see a complex interaction between different areas of the brain. It looks as if there are different functions that are activated depending on the situation. As humans are creatures that make independent decisions, we can expect that there are opposing poles that are activated as required, allowing us to choose sides. If we observe the decision-making behavior of different people, these alternatives become apparent.

- Orientation: rationality or empathy

- Relationship: belonging or recognition

- Development: enforcement or safety

This results in six preferences, most of which develop their own strengths from birth. As the fulfillment of each of these orientations is vital, we speak of basic needs.

- Rationality: If we do not perceive reality, we are helplessly lost.

- Empathy: We need to assess the effects of our actions in order not to be attacked by others.

- Belonging: We cannot survive in this world alone.

- Recognition: Even as a small child, we would die if we were overlooked.

- Enforcement: If you want to live, you have to actively provide for your needs.

- Safety: If you want to survive, you have to be aware of dangers in good time and react appropriately.

In our dreams and fantasies, we sensing these opposing forces as persons or personality traits. C.G. Jung described them as archetypes, which have been sensed in this way by people across cultures at all times. For example, the type responsible for communicating the belonging side in Greek mythology is Hermes, the messenger of the gods, in Norse myths it is Loki and the Romans knew Mercury, the bearer of news. The enforcement side is represented by Thor, Mars or, among the Greeks, Ares, who, as gods of war, also fight for their goals when necessary.

We can imagine the two of them meeting with the other four representatives in an old knight’s hall and taking their places according to our personality. This could look like this for the philosopher:

Rationality is in the chair. On the other side of the table sits empathy as the opposite pole. To the right and left of the ‘boss’, belonging and rationality sit opposite each other. Enforcement and safety have their places next to them.

It is therefore best for the philosopher to keep an eye on all basic needs and, if necessary, provide clarification and make well-balanced decisions.

These meetings of the inner team with the usual discussions and the struggle for the best possible decision happen unconsciously. Our ‘self’ moderates these processes and uses common goals and values that are accepted by everyone in the inner team. This works well when everyone involved gets their due.

To achieve this, it is important to integrate all conflicting aspirations into an overall picture (identity) and to commit to common goals.

All basic needs are active in our unconscious. Otherwise we would not have survived childhood. Each member of the inner team has their own specific experience of the questions: What do I need to do in order to

- orient myself in reality,

- integrate myself,

- be valued,

- assert myself,

- avoid danger,

- live in harmony?

From childhood, we train the behaviors that seem best for each need after a few tests, developing skills that can also benefit the other members of the inner team:

-

Rationality (black) analyzes situations and ongoing change processes. It wants sensible solutions.

-

Belonging (yellow) ensures common ground through coordination. It takes care of communication.

-

Recognition (blue) is critical, strives for the best, compares and evaluates alternatives. It ensures quality.

-

Enforcement (red) fights to achieve goals. It has visions and becomes spontaneously active when we can win something.

-

Safety (green) is an attentive observer. It recognizes risks and ensures order and reliability.

-

Empathy (white) wants to act responsibly and observes possible effects.

This inner distribution of tasks happens unconsciously, and we only feel that our energy is flowing, that we are inwardly satisfied and that we are achieving our goals - as long as there is unity at this table.

The mythologies tell us that this is not always the case. Our bipolar decision-making system brings conflict. It is in the nature of the unconscious. Our conscious thinking is always called upon when this unconscious team is not in agreement. We experience through dreams, feelings or spontaneous questions that we need to consciously reflect on something in order for these six basic needs to agree on goals and paths.

…